What do we mean when we talk about a fair and sustainable economy? What does such a thing look like? This year we will be profiling examples of things that hint at what the new economy could be – real projects, businesses and policies that are ‘green shoots’ of that future.

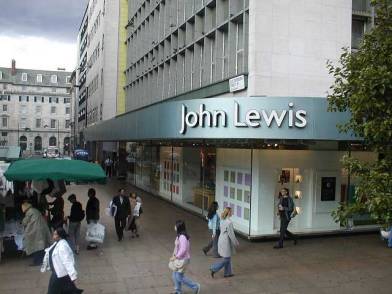

To start us off, we can look at one of Britain’s best-known retailers, John Lewis. Known for its high end department stores and Christmas adverts, its also a byword for an alternative form of capitalism. Politicians have even been known to refer to ‘the John Lewis economy’ as a way of explaining the fairer way of doing business that they have in mind.

To start us off, we can look at one of Britain’s best-known retailers, John Lewis. Known for its high end department stores and Christmas adverts, its also a byword for an alternative form of capitalism. Politicians have even been known to refer to ‘the John Lewis economy’ as a way of explaining the fairer way of doing business that they have in mind.

John Lewis, and its sister chain of Waitrose supermarkets, is owned by the employees. They are all partners in the business, a fact that they highlighted in their recent re-brand to John Lewis & Partners. Some see this as the secret to their customer service and quality, as staff are motivated to do their best for a company which is theirs, and in which they can take pride and satisfaction. When they do well, they all do well together and share in the profits, rather than the benefits of their hard work going to external shareholders.

This is what the founder, John Spedan Lewis had in mind, as he explained to the BBC in 1957 (pdf). The original John Lewis was an Oxford Street drapers, and John Spedan Lewis was apprenticed into the family business. He soon took issue with the way his father ran the company. He thought it was unfair that all the profits went to the family, while many of the staff were poorly paid. Surely this was profiting from the work of others and their wealth was undeserved.

Lewis began experimenting with ways to empower the employees, giving them more holidays and shortening work hours. He created an in-house magazine and a staff council to represent their views to management. The staff approved, but his father didn’t. He demoted his son from the flagship store to a smaller and less profitable one.

All that did was create a controlled experiment. The sister shop’s fortunes were turned around under Lewis Jr’s leadership, and his father had no choice but to recognise the benefits of his methods. In 1920 they rolled out a profit-sharing scheme across the whole business.

Lewis inherited the business when his father died a few years later. He was free to be more radical, drawing up a constitution that promised a living wage, and creating the John Lewis Partnership to transfer ownership to the employees. The partnership is an exemplary re-purposing of a business from serving profit to serving people. It reads: “The Partnership’s ultimate purpose is the happiness of all its members, through their worthwhile and satisfying employment in a successful business.”

John Lewis today may be an unhelpful symbol of middle-class consumerism to some, and like many retailers it is struggling with the changing ways that people shop. But it continues to prioritise employee democracy, shared profits, and good work. Behind it all is an inspiring story of a man who imagine a different kind of capitalism. John Spedan Lewis wanted to reduce inequality, arguing that “it is all wrong to have millionaires before you have ceased to have slums.” He believed in better work, making it “something to live for as well as something to live by.”

We could do with more business people like that, and more companies that put the wellbeing of people above shareholder value. Employee ownership could play a big role in reducing inequality, sharing wealth and creating good jobs that give people purpose and satisfaction.

- Originally posted on The Earthbound Report

No one can fail to be inspired by the John Lewis example. As the article says ‘it continues to prioritise employee democracy, shared profits, and good work’ and has done so for many years now.

A few questions that readers or viewers might help us answer:

What are the ‘good works’ it prioritises – a few examples?

How much are its top managers paid, and how much are its shop floor staff paid?

Does it do anything to challenge the long hours of work culture – as the Body Shop did at one stage?

What is its record on environmental sustainability? Not just in complying with the law and various codes of good practice, but in avoiding making money out of luxury end consumerist excesses that use precious resources?

All the time we have to bear in mind that they are operating in the real commercial world with all its inherent flaws. They are a real life example of an enterprise that ‘prefigures the kingdom’. We ask these questions not to cast doubt on their achievements but to either highlight their achievements or nudge them in new directions.

We look forward to hearing from you. any answers you might have to questions like these, and other positive examples from the world of business.

Tony Emerson

WordPress.com / Gravatar.com credentials can be used.

LikeLike